Self-help or Mormon propaganda?

The questions you need to ask yourself while reading "The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People" by Stephen Covey.

I was thirteen when I was first handed Sean Covey’s book “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens.” It was required reading for my health class and the only foray in that entire class into the world of “mental health.” As a teenager already diagnosed with depression, I felt alienated in the world and even more alienated as I read this book.

I remember feeling physically ill at the sight of the horribly designed cover with jeans (to make it feel edgy and cool?). And every time we talked about the book in class, I felt like something was wrong.

At the time, I thought that something was me. Other people seemed to be enjoying it and it was the first and only book in school that I didn’t finish. Now, as an adult, I know that what was wrong was the book itself.

This past year, I finally picked up Covey’s initial book (the adult version, written by Sean’s father): “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.” This book was filled with much of the same messaging as the teenage book: a classic self-help book with no acknowledgement of mental health.

As I started research Covey himself, a lot of the book started to make more sense. Covey himself grew up in and still was part of the Church of the Latter Day Saints (LDS) also known as the Mormon Church until his death. Many of these beliefs trickle down into his books, even though he has explicitly stated that his books are separate from religion.

Who is Stephen Covey?

With any book, it’s incredibly important to understand who the author is, but with “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People”, it’s crucial.

Stephen Covey grew up in the Mormon church and his parents were quite important in the church itself. His father was a leader within the LDS church and his mother was the daughter of Stephen L Richards, an apostle (called on by Joseph Smith’s nephew) and counselor to the First Presidency of the LDS church.

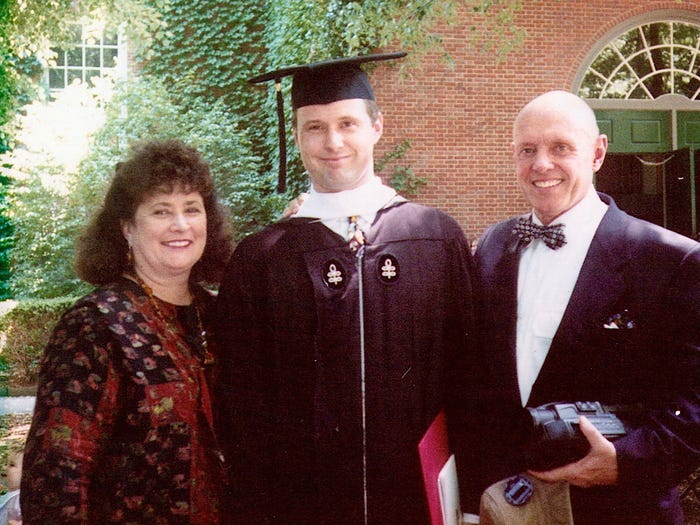

Covey’s education is vast with a bachelor’s degree in business administration, an MBA from Harvard Business School, and a Doctor of Religious Education from Brigham Young University. BYU is a university sponsored by the LDS church and is infamous for its conservative policies, including a Personal Conduct Policy that students must abide by which until recently (2021) had strict anti-LGBTQ rules as well. Not only did Covey obtain a doctorate here, but went on to be a professor at the school as well.

In his thirties, Covey carried on his parent’s impact in the Mormon church and served as the President of the Irish Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ.

Before and after “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People”, Covey wrote a variety of religious texts including a book titled “The Divine Center” (1982), which was written for a Mormon audience. While I haven’t personally read this book, it’s widely believed that this book formed the foundation upon which “7 Habits” was written as a few of the anecdotes and principles are the same.

After his success of “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People”, Covey followed in the steps of many self-help personalities and cashed in. He created a whole universe of books (including “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens” written by his son). This all led to him joining forces with Franklin Quest to create FranklinCovey, a business focused on leadership training. It’s a platform stuffed with courses, personal workshops, coaching services, and they even (horrifically) partner with schools, which is probably how I ended up reading that book in health class. Think of every red flag I’ve talked about in the self-help world and you can find it here.

Is “The 7 Habits” Mormon propaganda?

Let’s circle back to the origin of “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.” Like I said before, it’s widely believed that Covey’s book “The Divine Center” (a book written for Mormons) was the start of “7 Habits.”

Covey’s intention with “7 Habits” was to take these ideas and write it for a more general, secular audience. There’s two questions here:

1. Was the goal of this book to carry Mormon teachings to a secular audience without their knowledge in order to further evangelize the teachings of the church?;

2. If not, was Covey successful at removing religious teachings from the book?

In order to answer those questions, we need to first have an understanding of the Mormon church itself.

The LDS church was founded by Joseph Smith in 1830 and the core of the religion believes in the salvation of Jesus Christ and that the LDS church is a church established by Christ himself and that members of the church are living apostles and prophets. Because of this, church presidents are seen as modern-day prophets and church members are expected to pay 10% of their earnings (tithing) to the church.

Key beliefs and practices in the Mormon Church include, but are not limited to: believing that families are the most important unit in society; missionary work is an important practice where members are sent on “proselyting” missions around the world; abstaining from coffee and R-rated movies can be viewed to some as a good practice, and it’s encouraged by the church to keep a few months of food supplies in storage in case of emergencies.

(Of course, it’s important to note that these practices and beliefs don’t account for everyone in the church and as with all religions, there’s a spectrum of beliefs and practices)

However, like most religions, the church has a dark history. Church presidents have a history of child sexual abuse, some members still practice polygamy (sometimes including child brides), and the church has a history of overt racism, homophobia, and forced assimilation of Native Americans. Not to mention, there’s a whole history of financial controversy as well. To learn more I highly recommend the book “Under the Banner of Heaven”, and the documentaries “Keep Sweet”, and “Murder Among the Mormons”.

Now, to answer my two questions from above:

1. I think it’s impossible to know for sure whether or not Covey hoped to teach Mormon beliefs to a wider audience through a self-help book disguised as secular. However, based on the church’s strong push for evangelism and through Covey’s own history leading the Irish Mission, I don’t think it’s a stretch of the imagination to think that Covey may have done this.

In fact, in “The Divine Center”, Covey even states that, “I have found in speaking to various non-LDS groups in different cultures that we can teach and testify of many gospel principles if we are careful in selecting words which convey our meaning but come from their experience and frame of mind.”

While Covey has never explicitly admitted that this was the goal of “The 7 Habits” series, all evidence points to this being true.

2. If we were to give Covey the benefit of a doubt, I can still say that he wasn’t successful at making a secular book.

Throughout the book, many of the examples Covey uses includes faith in some way and at the end of the book itself, Covey even claims that his principles come from God: “As I conclude this book, I would like to share my own personal conviction concerning what I believe to be the source of correct principles. I believe that correct principles are natural laws, and that God, the Creator and Father of us all, is the source of them, and also the source of our conscience.”

Before we talk about the book, we can now assume a few things to be true: 1. Stephen Covey was a prominent member of the Mormon Church and 2. He used his influence to write books for people outside of the church, sprinkling Mormon teachings into a book meant for everyone.

“I’m not like other self-help books”

“The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People” is one of the most successful self-help books of all time with over 25 million copies sold. It’s the 5th most sold self-help book in the world (“Rich Dad, Poor Dad” beat it for the #4 spot).

In the beginning of the book, Covey actually criticizes the larger self-help industry in the same way I do. He claims that self-help books usually focus on image and positive thinking, in what he calls the “personality ethic.” However, that’s where Covey and I’s similarities end. The book’s main thesis is that true success comes from living by “correct principles” (again, principles he later claims come from God).

While Covey talks a tough game in the beginning, many of his teachings actually fall right back into typical self-help messaging:

He uses weight as an example of what someone may want to change: ‘““I’ve started a new diet–for the fifth time this year. I know I’m overweight, and I really want to change…I just can’t seem to keep a promise I make myself.’”

He romanticizes work and the importance of just doing work without question or complaint: “‘I want to teach my children the value of work…Why can’t children do their work cheerfully and without being reminded?’”

He is completely unaware of mental health and his advice is largely only helpful for neurotypical people. For example, he states: “We are not our feelings. We are not our moods. We are not even our thoughts.”

He completely disregards any systemic issues and privilege, once again saying that only we have the power to change our lives: “Our behavior is a function of our decisions, not our conditions.” ; “Where does intrinsic security come from? It doesn’t come from what other people think of us or how they treat us. It doesn’t come from the scripts they've handed us. It doesn’t come from our circumstance or our position. It comes from within.”

But on top of the usual self-help prattle, this book is also filled with things I didn’t expect: strange family relationships, extreme victim-blaming, and even the call to accept oppressive governments (all sprinkled with Mormon teachings on top).

Strange family relationships

We largely see Covey’s Mormon ideologies sneak (not so subtly) into the book when he talks about family and every day life.

Not only does he villainize TV because some “programs” “waste our time and minds and may influence us in negative ways”, but also reiterates that nothing is more important than family. He states: “A strong intergenerational family is potentially one of the most fruitful, rewarding, and satisfying interdependent relationships.”

I would be curious to know what Covey thinks a “strong” family looks like, because the stories he share portray anything but.

Covey consistently uses his children as examples and not always in a fond or respectful light. For example, he told two separate stories of how both his son and his daughter embarrassed him because one was socially “immature” and the other didn’t share her toys with other kids. In order to fix this problem, he and his wife prayed in order to be able to see his own kids in a new light.

On top of this, he also talks about the importance of having more of a boss relationship with his children rather than a nurturing one (it’s also no surprise that at least two of his children went on to work for him at FranklinCovey). This could be coming from either his Mormon teachings or his importance of teaching his kids to love work, or both. Either way, advice I hope people don’t take to heart.

Speaking of advice, he also shared a moment in the book in which he was giving advice to a married couple. In the middle of the conversation, the husband turned to Stephen and said, “‘‘Stephen, could you endure this kind of dumbness in your marriage?’…’Honey,’ he said to her ‘that’s your problem. And that’s the problem with your mother. In fact, it’s the problem with every woman I know.’”

Did Covey call-out the husband for the verbally manipulative, abusive, and sexist remarks. Of course not. He considered this marriage and his help with it a success.

Extreme victim-blaming

Like many self-help books, Covey quickly turns to victim-blaming and instead of looking at and critiquing larger systems at play that could be influencing people’s lives, turns to blaming the victim of those systems. However, he takes this one step further and particularly blames victims of oppression and occupation.

He builds up this argument by starting within individual selves and the narrative that people are responsible for their situations: “What I have seen result from the outside-in paradigm is unhappy people who feel victimized and immobilized, who focus on the weaknesses of other people and the circumstances they feel are responsible for their own stagnant situation.”

He states that people who blame what happened to them in childhood for how they are today just have a limiting belief with the common idea in self-help that: “It’s not what happens to us, but our response to what happens to us that hurts us.”

Going off of that, he argues that another limiting belief is blaming other things in our lives for our problems. Instead of complaining, he argues that we should just smile and accept the things we don’t like in our lives: “No control problems involve taking the responsibility to change the line on the bottom on our face–to smile, to genuinely and peacefully accept these problems and learn to live with them, even though we don’t like them.”

In a world without oppressive systems, maybe this idea works. But that’s not the world we live in today. And by smiling and accepting those harmful systems, we are limiting not only our selves, but the entire world.

Covey goes on to take this far beyond any other self-help author I’ve read and applies this thinking directly to oppressed people today and throughout history.

I’ve read a few self-help books that like to quote Viktor Frankl’s “Man’s Search for Meaning”, a book written by Holocaust survivor (I have yet to read this book, so I’m not sure about its messaging). However, Covey uses it to imply that Frankl was able to find meaning and dignity in his suffering, which allowed him to survive.

He follows up this story with a quote from Eleanor Roosevelt: “‘No one can hurt you without your consent.’” The indirect correlation being that those who suffered a genocide had to consent to the harm that was brought to them.

And Covey doesn’t just think this about one genocide. He even references modern-day examples of apartheid and occupation: “South Africa, Israel, and Ireland–and I believe the source of the continuing problems in each of these places has been the dominant social paradigm of outside-in. Each involved group is convinced the problem is ‘out there’ and if ‘they’ (meaning others) would ‘shape up’ or suddenly ‘ship out’ of existence, the problem would be solved.”

When it comes to occupation, when the occupiers leave the occupied land, then the problem is solved. It is not the occupied’s responsibility to do some internal enlightenment work and accept the world they live in.

As a successful example of this, he tells the story of Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt who “had been reared, nurtured, and deeply scripts in a hatred for Israel.” He led with the idea that he would never support Israel as long as they occupied Arab soil. Covey said that, “It was also very foolish, and Sadat knew it.”

Covey uses this as an inspiring story because Sadat rescripted himself through meditation and learned to “vacate his own mind” and brought forward the Camp David Accords “one of the most precedent-breaking peace movements.”

In reality, The Camp David Accords were a series of political agreements that determined the future of Palestine that were condemned by the United Nations because guess who wasn’t a part of the negotiations? Palestine. The UN also condemned it because it didn’t meet the Palestinian rights and a comprehensive solution to peace due to Israel’s continued occupation.

The acceptance of oppressive regimes and governments does not make an individual more enlightened or the world a better place. It only helps keep corrupt governments and people in power.

When I first read “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens” in middle school, I knew something was wrong. At the time, I did what Covey would have wanted me to and blamed myself. However, with a new lens of understanding not only the self-help industry as a whole, but Covey himself, I now know I was wrong.

Most self-help books are sinister because they share messages that diminish people’s experiences, disempower them, and brainwash them into thinking they themselves are the problem (when many problems lie within the systems we live in). Stephen Covey’s “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People” is even more sinister in the fact that it’s a collection of all of these messages with the added bonus of being Mormon evangelism disguised as a secular self-help book.